Found in a basement almost by accident in 2014, the Lost Dungeons of Tonisborg (2022) is the creation of Greg Svenson, and offers ten levels of that survival horror early role-playing games were great for. It was thought lost for over thirty years. Currently, I've run two Wight-Box parties on the first level, and only three characters survived, so it has the right stuff.

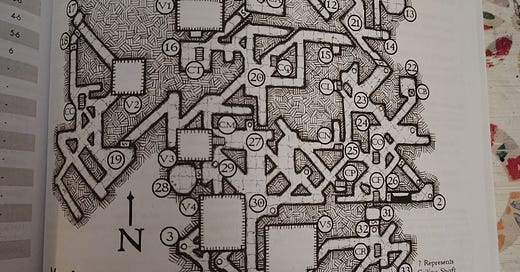

For my purposes, I'm interested mainly in the maps, not so much the accompanying rules on how to run his game. What I like in particular about it is the insight it gives into early dungeon design. Most of us think of the right angles, horizontals, and perpendiculars of a more lawful design, but when you only have a mapper and this is the map, you are in for a nightmare:

This is why we track rations and encumbrance.

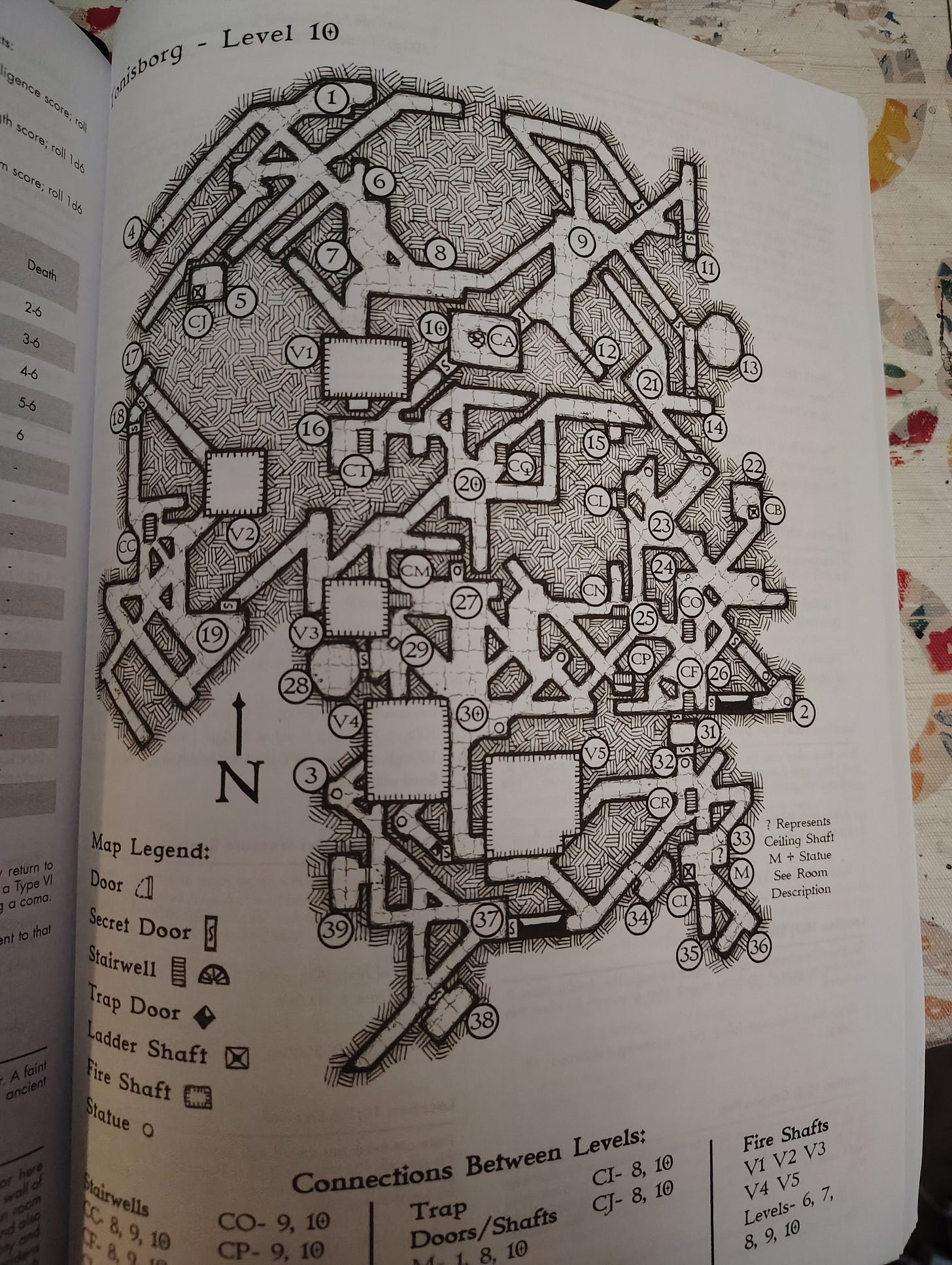

It’s delightful how chaotic the dungeon becomes as one descends deeper, culminating in this. I would recommend the book mainly for the dungeon itself, as well as some extra lore from the Blackmoor Bunch.

Blackmoor Foundations (2024) is a bit of an oddity. I did expect more primary sources, which the book did provide, though I was hoping for some kind of comparison between the Blackmoor published by TSR and Arneson's known notes. There are also large segments of the book which are just wasted space, and should have been filled with art or perhaps some other known drawings by Dave Arneson. It almost comes off like a little catalogue.

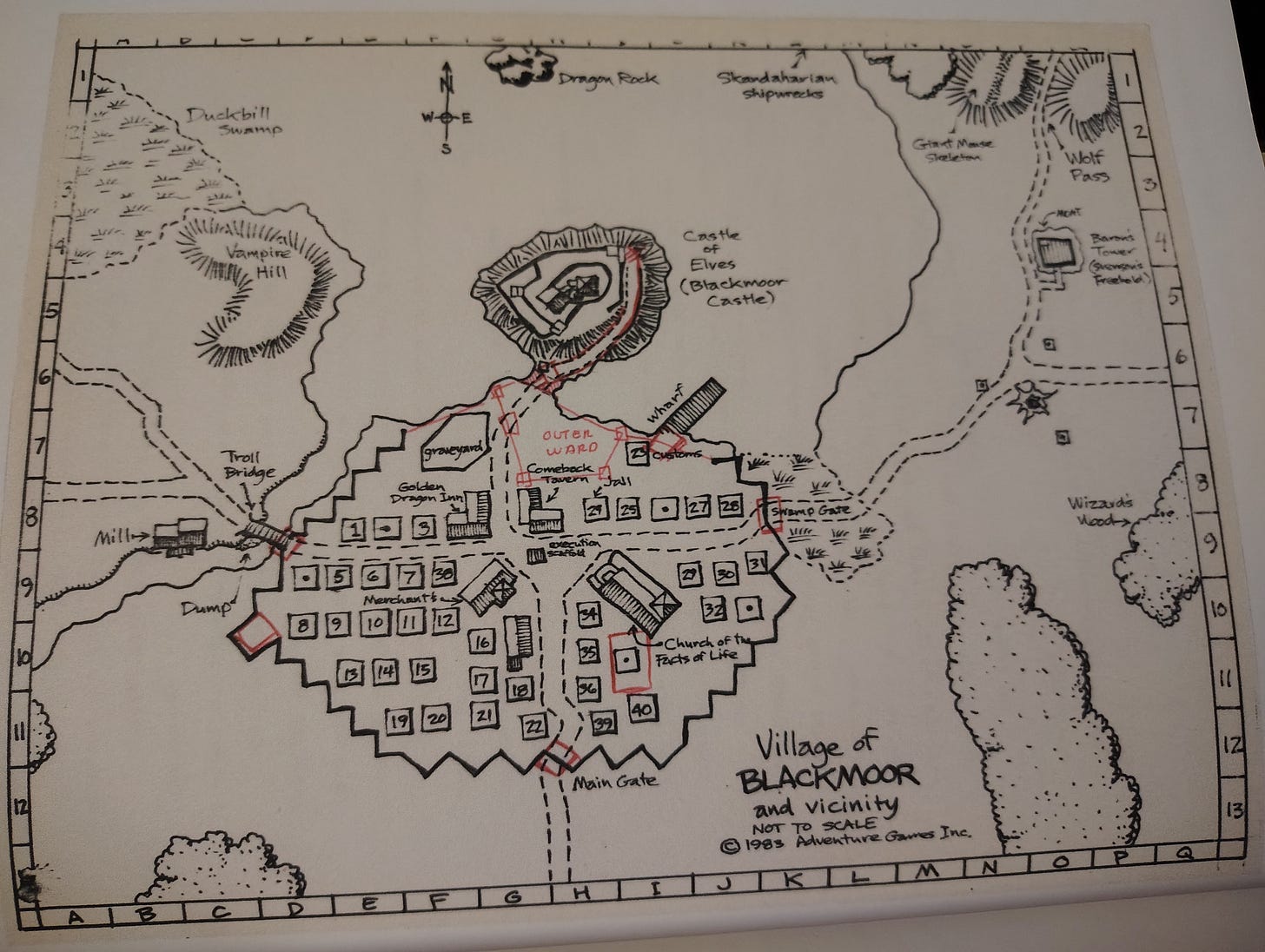

Despite working hard to demonstrate Arneson's creativity and ability, the book does not really address a central issue with him as a source: His secretive methods almost prohibit mimicking his game, which must be related to Arneson's writing habits. That is, if we can't derive his play style from his own notes, how would Gygax have felt after receiving them? Then, later with the Blackmoor supplement and needing Tim Kask to edit it? What it does show is the evolution of the region of Blackmoor:

Not found, however, is a dungeon map, though this can be inferred from Tonisborg or even the original Dungeon! board game.

Fellowship of the Thing, along with Rob Kuntz, have been working for some time to demonstrate how critical Arneson was to the creation of D&D. Since the milieu surrounding the game's creation has, for me, always included him to an extent, I am taking them at their word about the dispute. At the time of writing, I have not read Kuntz's book on Arneson, which is only available as a PDF. Perhaps the easiest thing here would be to quote Arneson's quip at the beginning of the Blackmoor documentary, since he has court documents for that purpose:

“Role-playing games first began in 1971. Don’t ask me how I know, because I’m the one who did it, thank you very much. All my dates are backed up by court documents, thank you.” (Secrets of Blackmoor: The True History of Dungeons and Dragons, 2019)

Compared to Tonisborg, I think the price point is harder to justify with the Blackmoor book, unless we take it as a specialist piece with a very niche audience. It comes off like a limited product for a small audience, and $40 could get me another AD&D orange spine book.

Admittedly, that audience includes me.

Now, there is something bugging me about reading Arneson research, and it comes down to how inscrutable his gaming method was. Griff terms it "Informal" (pg. 1) and that may hold the key to the relationship between Gygax and Arneson. See, games when published must be formalized and written with as much clarity as possible. Gygax receiving dozens of papers which he then had to interpret and beat into the shape of OD&D was the necessary step to bringing it to market. When Arneson complained about a lack of input on the final product, can we blame Gygax when thousands of 1974 dollars have been invested for those thousand copies which would change the face of gaming?

If anything, the relationship comes off to me as the motivated businessman Gygax teaming up with the brilliant-but-chaotic designer Arneson. This then implies that Arneson would have trouble sending clear notes in a readable form because of how he did things, which is admittedly sui generis. Still, Tim Kask was tasked with editing the Blackmoor supplement, and it seems from that point on Arneson would gradually be pushed out of TSR in a rather Japanese way: boring busywork.

As an experiment, let's assume for a moment that Gygax set up a game room and had Arneson scheduled to run Blackmoor sessions for staff, one of whom would be a recorder for the session. Surely, something useful would have popped up that Arneson could have then contributed to the next supplement? It seems like his mind needs the game situation to flourish, much like how modern athletes can't explain what they do, but you can see it on the field.

It falls into place for him only during the act itself.

Beyond that, I really can't blame Arneson for wanting his royalties as promised. We can of course debate the AD&D royalities case, though even there Gygax could not escape the fact that the game was built upon and derived from what the two of them made together.

While I can recommend Lost Dungeons of Tonisborg for its old-school dungeon design, Blackmoor Foundations should be considered a specialist source, so purchase that if you want to know a bit more about it, or if you’re a fan of the best D&D setting, because Blackmoor is Mystara’s distant past. If you’re also interested in his methods of description, which his group always enjoyed, there are some scanned pages of his writing (pg. 46).

I suppose it’s a good idea to take a moment and take stock of where I am with all these books I’ve been reading and reviewing since December. What I think a good synthesis of all these books needs to do is layer up what is going on in America at the time, the progression of the wargaming hobby, and the product line of D&D in order to get a fuller picture of what is going on when. A simple use of timelines will help quite a bit, and I think adding in little cross sections detailing how the game changed over time will be very helpful. Let’s be frank, the survival horror I refer to above is so far removed from the superhero game that is the fifth edition, it’s beyond apples and oranges, and more like a regular Joe going up against the Hulk. Resource management and gameplay phases also gradually get sidelined, and I think using the DMGs as sources will be rather helpful, until the whole “Actual Play” nonsense began.

But, whatever I will produce has to still be readable and unburdened by going into too much detail, which is the fault of any Annales history. The whole thing will have to culminate in the flops and mistakes which led up to the fiftieth anniversary being a wash, and the new edition of the game getting a lukewarm reception as they try to take D&D online and lock players into the trap of “recurrent user spending,” which has plagued videogames for so long.

I have Designers and Dragons on the docket next, and that one may be a rather quick read because it’s about the industry in general, while I’m primarily interested in the granddaddy of it all. That, and Games Workshop.